Soda Tax Helps Map Seattle’s Healthy Food Environment

One goal of Seattle’s sweetened beverage tax is to expand access to healthy and affordable food. To guide allocation of tax revenues to support this goal, the City asked researchers at Public Health – Seattle & King County and the University of Washington to study the healthy food environment in Seattle neighborhoods. In their report, the researchers addressed 3 questions:

Is healthy, affordable food more available in some Seattle neighborhoods than others?

Who in Seattle has trouble paying for food?

What are the concerns and capacities of Seattle’s food banks?

Is healthy, affordable food more available in some neighborhoods than others?

Yes, location does make a difference. Public Health researchers mapped Seattle neighborhoods where poverty, relatively long travel times, and high concentrations of food outlets with few healthy options may limit access to healthy foods.

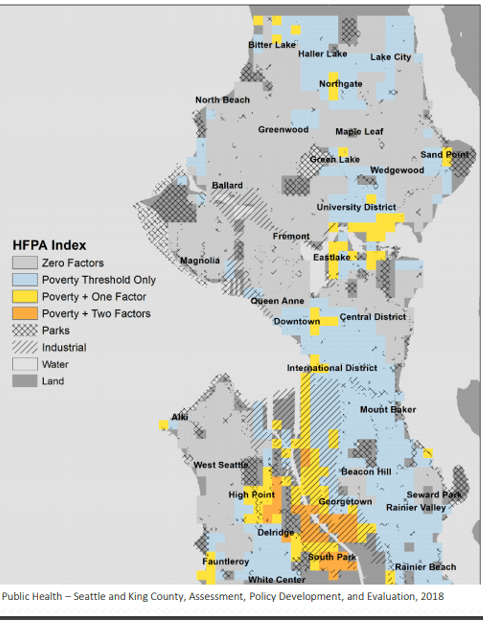

Mapping Three Barriers to Healthy Food Access

The map identifies neighborhoods where at least 1 in 4 households lives below 200% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines (for a family of 4, income less than $50,200 in 2018, shown in pale blue on the map) and highlights neighborhoods with 1 or 2 additional barriers to accessing healthy food: (a) at least 10 minutes’ travel time to the nearest healthy food retailer; and (b) a high percentage of food retailers without a produce section. Neighborhoods with all 3 risk factors (orange) – including South Park, Georgetown, Delridge, and High Point – were clustered around the Duwamish waterway. However, a patchwork of low-income neighborhoods with 1 additional risk factor (yellow) showed up across the city. For example, the north end has several “pocket” neighborhoods where low-income residents are surrounded by more economically secure neighbors, but may face challenges in accessing healthy foods, especially if they rely on public transportation.

Taking a different approach to the same question, University of Washington researchers conducted in-person audits of 134 food stores across the city (about 27% of all Seattle food stores) to look at the availability and costs of 25 healthy-food items such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, protein, and milk.

In-store availability

Healthy foods were more available in bigger stores (warehouses / superstores, supermarkets, and grocery stores) than in drug stores and small stores (convenience, gas stations).

Stores in low-income neighborhoods were less likely than those in middle- and upper-income areas to carry healthy food items.

As the neighborhood proportion of Black and Hispanic residents increased, the likelihood of finding healthy foods in stores decreased, although this tendency was not statistically significant.

When researchers looked at results by Seattle Council Districts, they found that healthy foods were least available in stores in Council District #2 (southeast Seattle, including the east bank of the Duwamish) and Council District #5 (north Seattle from Puget Sound to Lake Washington), and were most available in stores in District #4 (Northeast Seattle, including the University of Washington) and District #6 (Northwest Seattle, Ballard and adjacent communities). [Council Districts are shown on the food bank map below.]

Costs

In general, prices of healthy foods were lower in supermarkets than in smaller stores.

Although prices generally didn’t differ by neighborhood income, the costs of some healthy foods were slightly lower in low-income areas and higher in higher-income areas, and vegetables cost significantly more per pound in middle-income neighborhoods than in low-income neighborhoods.

While prices for most healthy foods prices were similar in neighborhoods with high, medium, and low concentrations of Black or Hispanic residents, costs for grains and eggs were lowest in neighborhoods with high concentrations of Black or Hispanic residents.

Who in Seattle has trouble paying for food?

Researchers found that the highest risk for what’s known as “food insecurity” (running out of food and not having money to buy more) occurred among people of color; families with young children; older adults; adults who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual; and in households where adults reported low income and/or low educational attainment.

However, food insecurity isn’t limited to people who qualify to receive benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, previously called “food stamps”). Public health researchers determined that more than 13,000 Seattle residents who make too much to qualify for SNAP reported food insecurity, which didn’t drop to fairly low levels until 300% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines (less than $75,000 for a family of 4 in 2018). Among people of color, the “food security gap” was even wider, extending to 400% of Federal Poverty Guidelines.

What are the concerns and capacities of Seattle’s food banks?

Seattle Food Banks and Areas of Concentrated Poverty

Last year, Seattle’s 30 food banks were surveyed about their capacities and demands. Respondents reported distributing a total of more than 23 million pounds of food – an underestimate of citywide distribution since not all food banks completed the survey. Combining survey data with staff interviews and client discussions in 5 languages, researchers also learned that:

Visits to food banks increased last year, according to more than 60% of food banks that responded to an online survey. Food bank staff specifically mentioned more visits from older adults, people who were experiencing homelessness, and those who were living near the northern and southern borders of the city.

To meet current demands, food banks would need to invest in staffing and salaries as well as more space and purchasing power.

Food banks could benefit from coordinated systems of distribution that target areas with the greatest needs (concentrations of poverty shown in darker shades of blue on the map above).

Clients said that they appreciate a dignified food bank experience – often described as a grocery store model that allows client choice. Clients also value food safety and quality, cultural relevance, and convenient access. Specific requests included more protein, more fruits and vegetables, options to get foods that don’t require cooking, and evening and weekend access.

At the February 27th presentation of the report’s findings to the City Council’s Finance and Neighborhood Committee, City Council members voiced concerns about food insecurity among older adults and families with children. They also expressed support for food banks, and noted their value in strengthening community connections.

Over the next several months, the City will consider applications for funding to expand access to healthy and affordable food. Coordinated with the report’s release, the City of Seattle Human Services Department released a 2019 Food and Nutrition RFP that focuses on Seattle Emergency Food Systems.

View the full slides, written report, and video of the presentation on healthy food availability and the Seattle food bank network to the Finance and Neighborhood Council Committee. The research team includes Jesse Jones-Smith, University of Washington and Nadine Chan, Public Health – Seattle & King County along with Seattle Children’s Research Institute and the UW Center for Public Health Nutrition. Communities Count provides data on food bank trends, SNAP/Basic Food participation, use of free and reduced-price school meals, WIC participation, and food insecurity/hardship in King County.